18 January 2018

Bismillaahir Rahmaanir Raheem

Allahumma salli alaa sayyidinaa Muhammadin wa baarik wa sallim

Maktab Programme Outline

1. Introduction

Majlis ul Ulamaa recognizes the post-industrial era that underscores the importance of knowledge in the development of individuals and society. It also notes the emergence of ubiquitous technology-based media and channels of communication that present a platform for increasingly global access to information, interaction and influence.

In this regard, we recognize the need to reinforce Islamic values and beliefs that would not only serve to form the foundation for behavior and thought of individuals, but also empower them with the necessary perspectives and paradigms that would help them to live a meaningful and purposeful life for the benefit of themselves, their families, their communities and society as a whole. These help to ensure that persons can – individually – strive to earn the best in this world and in the hereafter.

1.1 Ages and Stages of Development

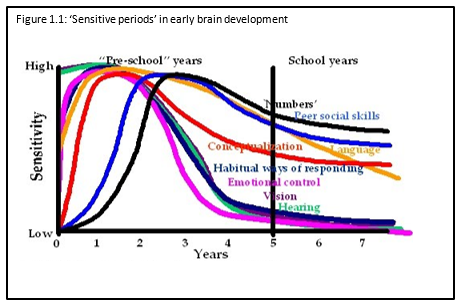

Studies which are focused on cognitive development and related aspects within neuroscience attempt to map the ages at which various types and intensity of learning occurs. Many such studies conclude that the formative years of individual behaviour and values are those pre-pubescent and adolescent years. Within this context, there is need to articulate the ages involved within which such development occurs, and the type and intensity of learning that maps to the age in question (Radley et al 2004; Bock 2005).

The age brackets are clustered into several key statistical groups which relate to most children, mapped in close approximation to school levels, and generally include the following:

· 3-6 years old (pre-primary to 2nd year)

· 7-10 years old (primary school)

· 11-14 years old (secondary school and age of puberty)

· 15-18 years old (secondary school, entering ‘age of adulthood’)

· 18+ (post-secondary academic or vocational school)

1.1.1 Early Childhood Development

According to Harvard Education Centre on the Developing Child (The Science of Early Childhood Development 2007), “In the first few years of life, more than 1 million new neural connections are formed every second. After this period of rapid proliferation, connections are reduced through a process called pruning, so that brain circuits become more efficient. Sensory pathways like those for basic vision and hearing are the first to develop, followed by early language skills and higher cognitive functions. Connections proliferate and prune in a prescribed order, with later, more complex brain circuits built upon earlier, simpler circuits.”

The type and intensity of learning is also alluded to here, and identifies sensory development, language and higher cognitive functions. These learnings have been identified by various studies to include the following (Nash 1997, Early Years Study 1999, Shonkoff 2000):

· Language

· Vision

· Hearing

· Numbers

· Peer Social Skills

· Conceptualisation

· Habitual ways of responding

· Emotional Control

Harvard Education (ibid) studies suggests that these competencies largely need to be looked at holistically, since “…together they are the bricks and mortar that comprise the foundation of human development. The emotional and physical health, social skills, and cognitive-linguistic capacities that emerge in the early years are all important prerequisites for success in school and later in the workplace and community.” Graphically these can be represented in the following:

1.1.2 Teen development

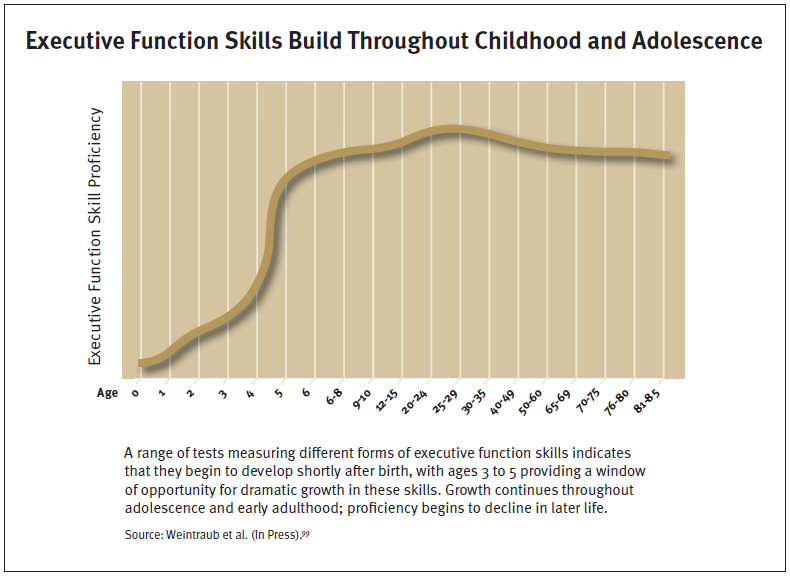

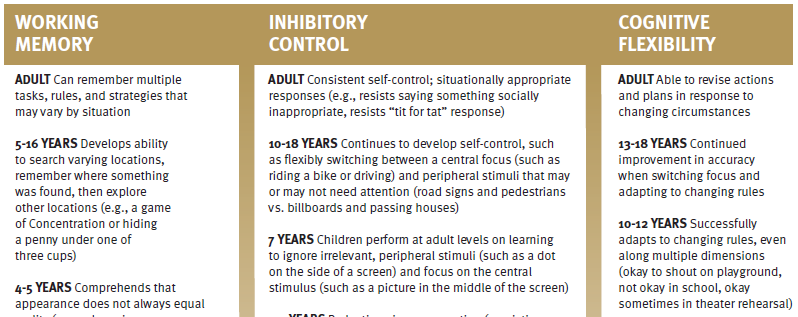

Teen development in a secular context tends to focus on knowledge and task capabilities – what some refer to as ‘executive functions’. Scientists have recognized three dimensions that are frequently highlighted:

1. Working memory is the capacity to hold and manipulate information in our heads over short periods of time. It provides a mental surface on which we can place important information so that it is ready to use in the course of our everyday lives.

2. Inhibitory control is the skill we use to master and filter our thoughts and impulses so we can resist temptations, distractions, and habits and to pause and think before we act. It makes possible selective, focused, and sustained attention, prioritization, and action. This capacity keeps us from acting as completely impulsive creatures who do whatever comes into our minds.

3. Cognitive or Mental Flexibility is the capacity to nimbly switch gears and adjust to changed demands, priorities, or perspectives. It is what enables us to apply different rules in different settings. We might say one thing to a co-worker privately, but something quite different in the public context of a staff meeting.

Executive function skills do not just appear in adulthood and they are built over time. Executive function skills are also highly interrelated. (Harvard University 2011)[1].

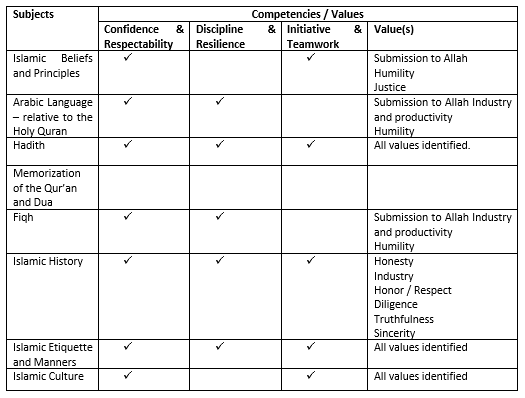

1.2 Development Competencies

Much of the development occurs in the context of future benefit and the competencies required – particularly in terms of technical competence in a specialized area, alongside the social interaction with family, within communities and in the workplace. To this end, there are some specific capabilities which need to be developed as persons mature, so as to become functional members of society, and more pertinently within Islam to live a life that is pleasing to Almighty Allah (swt). These capabilities we understand to include:

· Confidence and Respectability

· Discipline and Resilience

· Creativity and Innovativeness

· Initiative and Teamwork

As well, certain values that speak to morality and virtue are espoused within Islam which persons must strive to inculcate, and include:

· Submission to Almighty Allah

· Honesty and truthfulness

· Industry and productivity

· Keeping your word

· Charity to those in need

· Humility

· Justice

· Social Responsibility to all stakeholders

· Mutual Consideration in all affairs

It must be noted that more comprehensive treatment of these virtues would focus on those values and behaviours which we must inculcate (of which some are mentioned above) as well as which we must avoid. For more detailed treatment of these, many publications are available for reference.[2]

For these to be achieved individually and collectively, there are some key subjects that need to be covered, including the following:

· Islamic Beliefs and Principles

· Key Personalities (and their behavior) in Islamic History

· Islamic Etiquette and Manners

· Arabic Language – relative to the Holy Quran

· Performance of Prayer

· Islamic Culture

As well, the maktab can introduce or reinforce behaviours relative to social issues and challenges to which the age groups are exposed. These include:

· sexual promiscuity

· pregnancy

· substance use and abuse

· peer and media influence

· suicide

· poor self esteem

· sexual abuse

· divorce

· poverty

· violence and physical abuse

· delinquency – especially with respect to education system dropout or non-performance

1.3 Maktab Programme Design and Fit to Students’ Lives

The Maktab programme, in addition to considering the aforementioned ages, stages and focus of development, also has to consider the role and fit of the Maktab programme to the lives of the children in the national context.

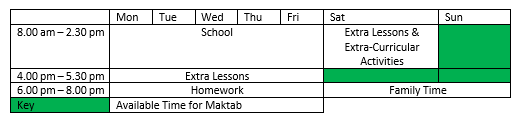

1.3.1 Time & Availability during the Week

Currently the dominant social institution impacting the lives of the children in the identified ages are the school and family constructs. The school by far dominates the greater part of the waking lives and learning times of children within the age brackets identified. As it is currently, many students attend school, attend extra classes to supplement school learning, and may have extra-curricular activities (such as sporting and gaming) which they pursue. These demands can span up to 12 hours of a student’s life per day five days per week, and an additional 3-5 hours on Saturdays. This can be intense for children within the 3-18 year brackets, and leaves little time to enjoy other facets of life, let alone additional study of Islam.

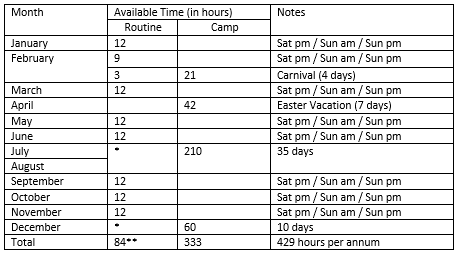

1.3.2 Time & Availability during the Year

The maktab would have to consider competing interests and times on the lives of children and families. The calendar year for the maktab should be designed assuming that attendance would vary during the course of the year. It can be expected that children would miss one weekend a month (i.e. present for a total of 40 weeks a year). It can also be expected that children preparing for examinations would be under additional pressure and parents may decide to relieve them from maktab during such time periods. This is assuming that the maktab is associated with additional learning (which may detract from a core academic focus) and presents additional forms of pressure on the child. This can account for approximately 2 weeks in each term (6 weeks total) and an additional 10 weeks (April – June) for certain children in the period leading up to end-of year or national examinations.

There are periods during the year where children are on vacation from school, and have considerable time to explore other pursuits. Travel, children and youth camps dedicated to study, sport and other interests all feature. These times can be capitalized for the benefit of the maktab programme, but would require attention to logistics and supervision to ensure the objectives are fully realized.

|

February/March |

3-5 days |

Carnival |

|

March/April |

2 weeks |

Easter Vacation |

|

July & August |

8 weeks |

‘Summer’ Vacation |

|

December |

3 weeks |

‘Christmas’ Vacation |

This means that there are approximately 13 weeks of time available for children to be engaged. If we were to subtract 1 week in each period for back-to-school preparation, this results in a possible 10 weeks available for engagement, staggered throughout the year, and with heavy emphasis (6-7 weeks) in the July and August period.

The time availability and opportunities for engagement would therefore do well to consider a maktab time allocation thusly:

*Normal scheduled maktab time would be replaced by maktab camp time activities and agenda. For e.g. weekday camp sessions would replace the weekend 3-hour sessions for July/August.

**It is expected that 12 hours of maktab time per annum would be deducted to cater for the month of Ramadan

1.3.3 Family Commitment

We note that the family unit is evolving in the society, with many homes having both working parents, and others operating as single-parent families. The traditional Muslim family is also an evolving institution, since it is more common and with increasing frequency that Muslim families comprise a ‘born Muslim’ and a ‘revert’ partner. The extended family which traditionally provided a layer of additional support and influence is also being fragmented, due to migration within and outside of the country.

The work hours of parents can be significant, with parents having to work late requiring persons (extended family who may or may not be Muslim) to care for the children (or alternatively keep them at the workplace where possible) as necessary. This affects not just the quality of parent-child interaction, but also the exposure and influence exerted on the child, as well as other areas including which mosque the parent identifies with more as a part of the community. The extend of parent or other guardians’ exposure to Islamic teachings and values also have an impact on the extent of exposure and inculcation of Islamic teachings in the home and family environment. In many respects, the reverting parent has to be exposed to Islamic principles, practices and beliefs themselves if any influence has to be extended by them onto a child. Where extended family or guardians are not Muslim, the influence can be to other value and belief systems entirely.

1.3.4 Peer Influence

In addition, other influences on children are evolving as well. Peer interaction from others of different backgrounds, belief systems and values are as manifest today, and are competing (and in many cases influenced as well) by the emerging technology diffusion within society. Gaming, entertainment and social media, virtual and augmented reality applications present additional interests to children – directly in terms of the entertainment to which they are exposed, as well as indirectly – forming the basis for, and being the subject of peer interaction and conversations that may be had. Parental influence can vary, depending on the family structure and tone of influence being exerted.

1.3.5 The Evolution of Learning

There has been a gradual shift from the rational to empirical methods of learning, and the emphasis away from rote learning to applicable skills and competencies. This, essentially encapsulated within the pedagogical philosophy of Constructivism, focuses more on student-centered learning and the ability of the teacher to capture the interest and passion of the student for the subjects being studied.

Related to this, it is recognized from research that attention spans vary as a result of variance in age, physical, mental and emotional development of the individual, as well as the nature of the subject being addressed. On average, it is recognized in research that the attention span grows for a period of 2 – 5 minutes for each year old that they are. Hence, the attention span can range from 4 – 10 minutes for 2 year olds to 20 – 50 minutes for 10 year olds. For adults, it is recognized that adults have attention span of 15-20 minute segments, following which a break in the session would facilitate a refocus on the matter at hand. These formats of delivery can span protracted periods of an entire work day (8 hours) to much longer periods for different individuals and professions.

1.4 Maktab, Mosque and Muslim Community

1.4.1 Traditional Maktab Model

The maktab has typically been focused on teaching Islamic principles and practice (with structured syllabuses being secondary to established books such as the Islamic Catechism etc.), and anchored in the mosque. Traditionally, persons from the community, already knowing and being involved in the mosque activities, would invariably send their children to the maktab as part of the requirements and affiliation with the community.

They would be involved in events, and witness the progress of the children in a public (typically group) display of recitals. On a day-to-day basis, children would share learnings of the day (once per week) and elaborate on the light refreshments provided. This model may still have a place in rural and ex-urban communities, but may prove less relevant to urban and suburban areas (which are typically representing a larger percentage of the population).

Regardless of geospatial residence, as the social institutions at the family, school and other institutions level evolve, the maktab model needs to keep abreast of changing roles if it has to continue to be a relevant institution that helps shape the development of the children and preserve Islamic values, beliefs and education.

1.4.2 Maktab Teachers and Teaching

Generally, the teachers of the maktab were the imam or other appointed persons who, typically individually, was responsible for setting the agenda, teaching the subjects and supervising the children in his/her charge. These individuals would also assume the responsibilities for managing the logistics and resourcing of initiatives that would be required at the venue, or on field-trips or assignments, as required.

It is a role that typically demanded dedication, commitment, creativity, discipline, attention to detail, marketing capability, teaching competence, negotiation skills along with a range of other skills and abilities to ensure that the maktab was kept running. It is not uncommon that these roles were assumed by persons in the face of antagonism and opposition from other members of the community, some even in senior positions within the community hierarchy.

In other instances, persons who were deemed qualified would assume the role and conduct the maktabs (sometimes at a cost), but with little oversight in terms of competencies targeted for development or periodic assessments on attendee performance.

These realities, building on the traditional maktab model, meant that development was measured against recall ability to narrate or operate at the mechanical level, with not much deeper thought or study being assessed or emphasized to gauge understanding, commitment and further involvement in the community.

2. Maktab Programme Design

The above influencing factors and development thrusts being considered serve to form the basis for the proposed development of the Maktab programme in terms of design, delivery and intended impact on the persons targeted.

2.1 Design Principles

· The Maktab as a social institution is being developed as a supplementary programme to existing educational programmes (in schools) to which children are required to attend.

The maktabs would focus on aspects of development that are not explicitly emphasized in these programmes or institutions, such as morality, virtues and character. Majlistt notes that these areas of attention require ongoing reinforcement and demonstration of examples to which the students of the Maktab can be exposed.

· The purpose of the Maktab is to support the development of a child and prepare them with the life skills to become good practicing Muslims and functional contributing members of society, through the introduction and/or reinforcement of the Islamic values and culture.

It is recognized that children attending the maktabs would be from diverse family or school exposure backgrounds, and would be as individuals at different stages of development

· The Maktab should fit the child’s development according to their age and competencies.

· Learnings across the different ages should accumulate over phases, building on what is known and reinforcing what is right according to Islam.

2.2 Operating Framework

Given the focus to instill values and behaviours, which requires ongoing reinforcement, suggests that the maktab should be an ongoing programme over the course of year, from the time the child is able to attend through to adulthood. As well, considering the structure of the secular education system, there are times when the maktab programme can be amplified or expanded, and other times where it can be throttled back to accommodate secular education examination demands. As such, we see the maktab programme operating on 2 levels:

· ongoing annual activities

· ‘vacation’ camp sessions that cater to students’ down times

Each would have its own sphere of focus, and would target different treatment of subject matter and student engagement. The main area of focus for the rest of this document would be that of the ongoing annual activities.

2.2.1 Ongoing Annual Activities Timelines – Annual Structure

The timelines for the structuring of a maktab programme takes consideration of the students’ timelines for the year. Based on the consideration of factors aforementioned, the suggested structure for the maktab programme is on a quarterly basis – i.e. every 3 months for the calendar year (or an average of 12 week cycles). These would be structured along the lines of:

· January to March

· April to June

· July to September

· October to December

This structure would allow for consideration in particular of the annual academic examinations periods for students, whereby demands are increased on their workload. We do recognize that some parents choose to continue to send their children to maktab, secular academic demands notwithstanding. We note as well other children are subjected to extreme stress and workloads that can compromise their performance. As a result, the April – June period is one that would have to be paid particular attention to by the maktab teachers.

2.2.2 Ongoing Annual Activities Timelines – Weekly Structure

Form the consideration of the weekly timelines and normal demands placed on children within the age brackets under consideration, the available times for optimal attendance seem to be Saturday afternoons or Sundays during the course of the day.

For these weekly sessions, the suggested time-period for the maktab is a 2 to 3-hour period, which would allow sufficient time for the impact to be had by the teachers on the students. These periods can be divided into 30 to 40-minute segments, which would allow for between to 4 to 6 sessions in the course of the student presence.

2.2.3 Ongoing Annual Activities Timelines – House Rules

It is normal in today’s context for parents who may not be as attached or involved in the routine mosque activities to have concerns regarding the safety of their children, and the temptation of any programme organizer to ‘cover-up’ incidents as a means of safeguarding the programme longevity. As well, the mosque which is largely unoccupied save the scheduled daily prayers (and select ones at that), can reinforce the risk to which students are exposed.

In this regard, the mosque maktab programme should consider the safety of students and the security of the compound and facilities being used, which would vary depending on the specific context.

As well, to mitigate the risk of improper conduct by and among students, and even by the adults charged with supervision, the maktab programme should have a senior representative of the mosque executive, or parent present for each session.

2.3 Maktab Subjects

2.3.1 Subjects to be Taught

To preserve Islamic learnings, values, beliefs and competencies, the following subject areas are identified that should be introduced to the identified age brackets of children:

|

Subject Areas |

|

Islamic Beliefs and Fundamental Principles · Articles of faith · Catechism · 5 pillars |

|

Arabic Language – relative to the Holy Quran, including: · Reading fluency of Arabic and Quran (starting from the alphabet) · Tajweed · Hifz · Qirat |

|

Hadith · See details in section 2.3.3 |

|

Memorization of the Qur’an and Dua · See details in section 2.3.3 |

|

Fiqh · Wudu and Salaat · Fasting |

|

Islamic History · Seerah · Stories of other Prophets in Islam · Islamic History after the Holy Prophet (pboh) (Khulfa I Rashideen) |

|

Islamic Etiquette and Manners · See details in section 2.3.3 |

|

Islamic Culture, including: · Islamic terms and events · Islamic Songs · Art and Craft |

2.3.2 Subjects Mapped to Competencies

These subjects map to the aforementioned competencies and values, either in terms of the content being delivered and/or in terms of the way in which the subject is delivered and taught. This is best considered at the syllabus stage, but a consideration of how these can be developed are considered following:

Finally, the maktab programme operating in a 2 to 3-hour period, having between 4-6 sessions over the period, need to be structured in such a way that students would not be overly exhausted with consecutive activities that demand similar skills. Rather, the teacher can schedule the activities / subjects to interchange various skill sets, so that students are kept engaged

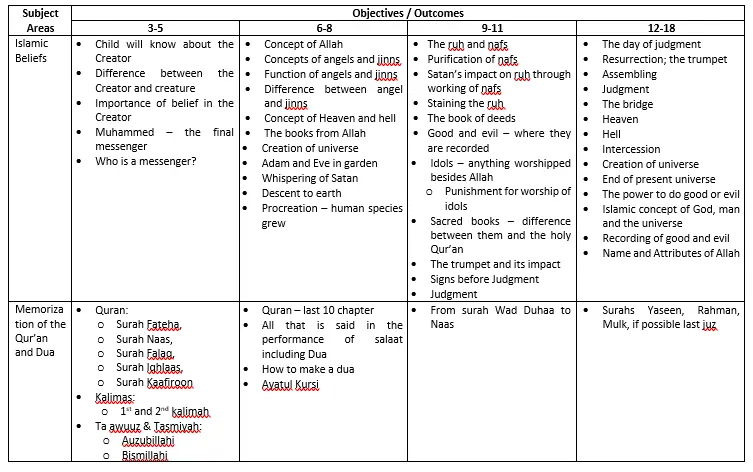

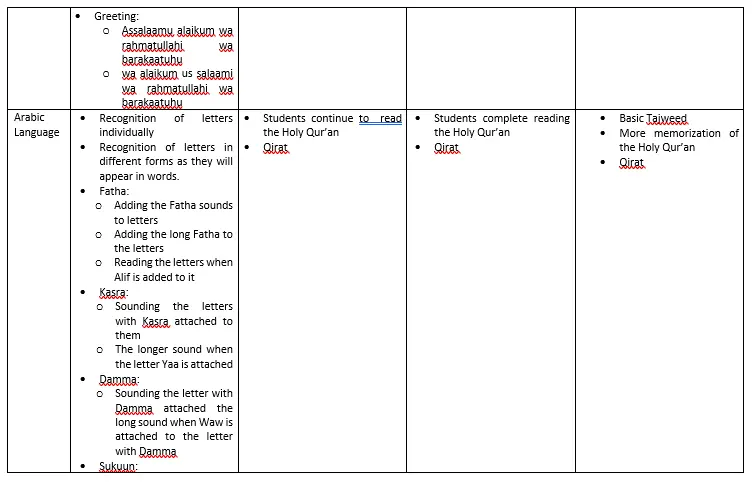

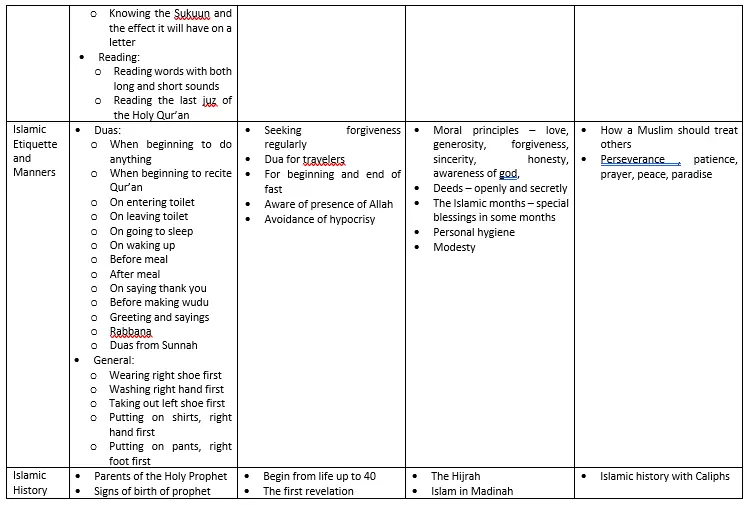

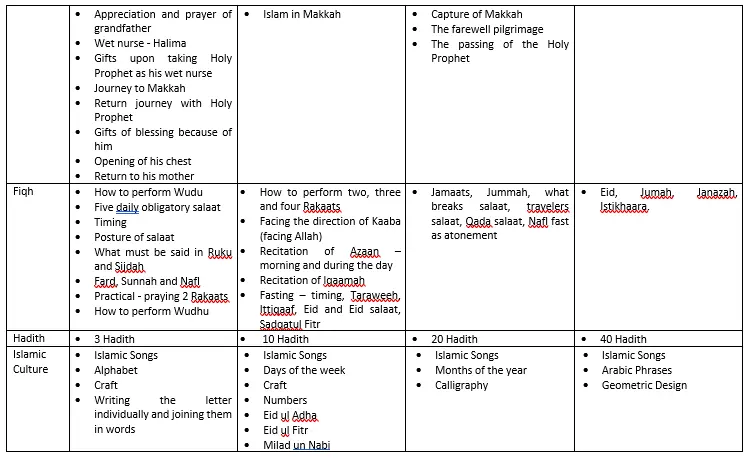

2.3.3 Objectives / Outcomes for various age groups

The graphics that follow outline what students of the Maktab programme are expected to know by the end of the duration identified, in each subject.

Allah knows best

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

[1] Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2011). Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” System: How Early Experiences Shape the Development of Executive Function: Working Paper No. 11. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu

[2] Dr. Ismail Mangera, (2006) Good Character: Compiled from the Teachings of Hadhrat Maulana Muhamed Maseehullah Khan, Idara Isha’at-e-Diniyat (P) Ltd., New Delhi